Psychoneurosis Letter

July 1944Dearest Reader,

Reading my grandmother’s words, it is clear how complicated and emotionally charged the term psychoneurosis was in 1944, She writes:

“You will note that Dr. Link, a noted psychologist, does not believe in the use of that term, that to call a man a ‘psychoneurotic’ is to go a long way towards making him one. A psychoneurotic is someone who thinks there is something wrong with them when in reality there is not… someone who is always worrying about themselves. In other words, someone whose thinking is all wrong.”

Her explanation reflects the public understanding of the time. There is a mixture of confusion, stigma and

oversimplification of a diagnosis that was quietly shaping the lives of thousands of soldiers and their families.

During WWII, psychoneurosis was one of the most common psychiatric diagnoses used by the U.S military. It was a broad term meant to capture everything from anxiety to panic attacks to what we now recognize as Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). But because the diagnosis was so broad and poorly defined, it carried enormous social weight. To many civilians, it suggested weakness and to the soldiers, it often added shame and suffering.

At the beginning of the war, the Army worked hard to avoid public discussion of the problem. Many psychiatrists were overwhelmed with men suffering from “combat fatigue” but newspapers were discouraged from covering the issue. The War Department feared that acknowledging widespread mental strain would hurt morale or be interpreted as unmanliness. For the first years of the war, there was essentially a blackout in public reporting on psychiatric casualties.

By mid-1944, the time of my grandmother’s letter, the silence had begun to break. Articles about “war neuroses”, “nervous strain” and “psychoneurosis” started appearing in local papers, often with the message that echoed my grandmother’s, that worry itself could cause illness. This condition was seen as rooted in “wrong thinking” and that men should calm themselves and try not to dwell on their symptoms. These explanations were meant to destigmatize, but they also may have dismissed the real psychological injuries soldiers were experiencing.

During World War II, the U.S. Army discharged nearly 389.000 men for neuropsychiatric reasons. Of those, about 270.000 soldiers were labeled as psychoneurotic. It was one of the most common reasons for medical discharge and accounted for nearly 44% of all disability separations. Behind the scenes, military psychiatrists were overwhelmed. Historians estimate that over one million American service members experienced some form of mental breakdown, severe anxiety or combat stress reaction.

The term psychoneurosis began to fade after the war. In 1952, with the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, psychiatry began adopting more specific categories: “anxiety reaction,” “compulsive reaction” and eventually, “post-traumatic stress disorder, which was formally recognized in 1980. As the field evolved, psychoneurosis became recognized as too vague, too stigmatizing and too rooted in outdated ideas.

By the late 20th century, the word had virtually disappeared from professional use. It remains today mostly an historical reminder of the limits of medical understanding of the stigma soldiers faced through the language available to them.

Through my grandmother’s letters, I can see how one complicated and misunderstood word traveled through the news and doctors’ offices and was a part of my family’s story.

Dr. Nancy Watson

Rambling With Nan

Washington

Read More From Nancy

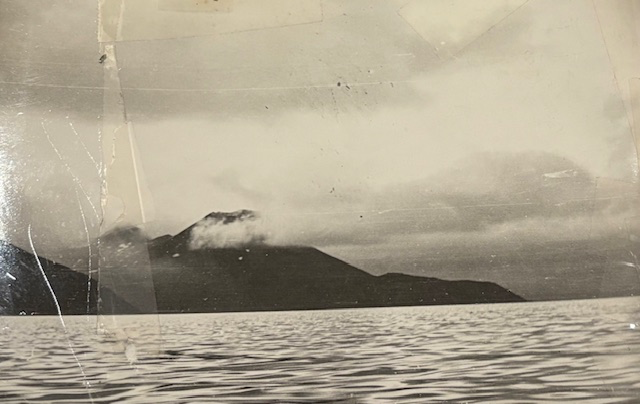

Eider Point on Unalaska Island – Aleutian Island

This photograph my father sent home is of water, land and sky and without the words on the back, I would not know where this was located. My father wrote on the back: “LOOKING FROM ISLAND AMAKNAK, DUTCH HARBOR ACROSS TO EIDER POINT ON UNALASKA ISLAND, EIDER POINT KNOWN AS FORT LEANARD OF “B” BTRY 264 CA” […]

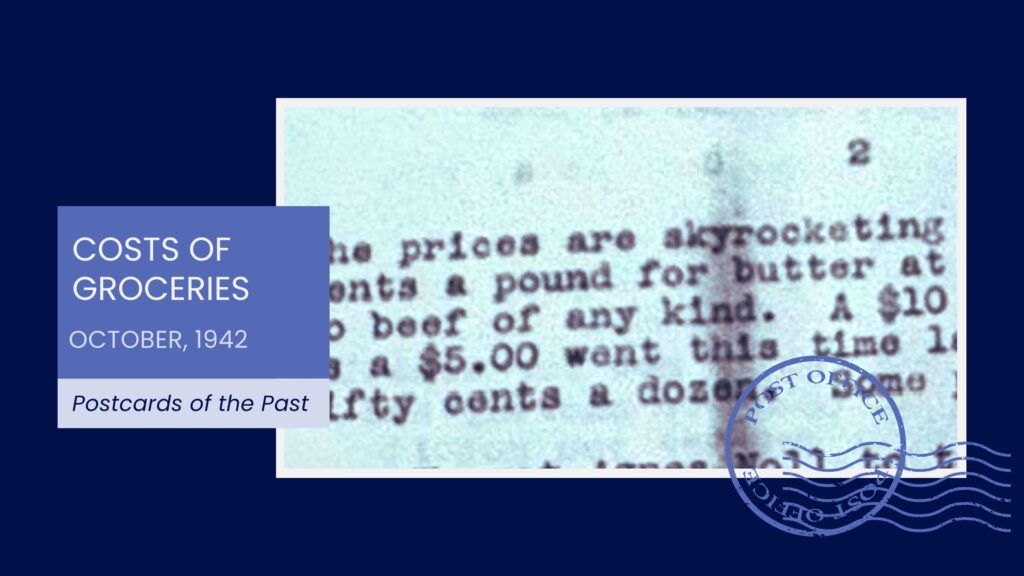

Costs of Groceries

In October 1942, as my father was stationed in Washington State, my grandmother wrote to him describing how profoundly life on the home front had changed. Her letter reflects a nation fully mobilized for war, where shortage, rationing and rising prices had become part of everyday reality. What she shared was not abstract, but lived […]

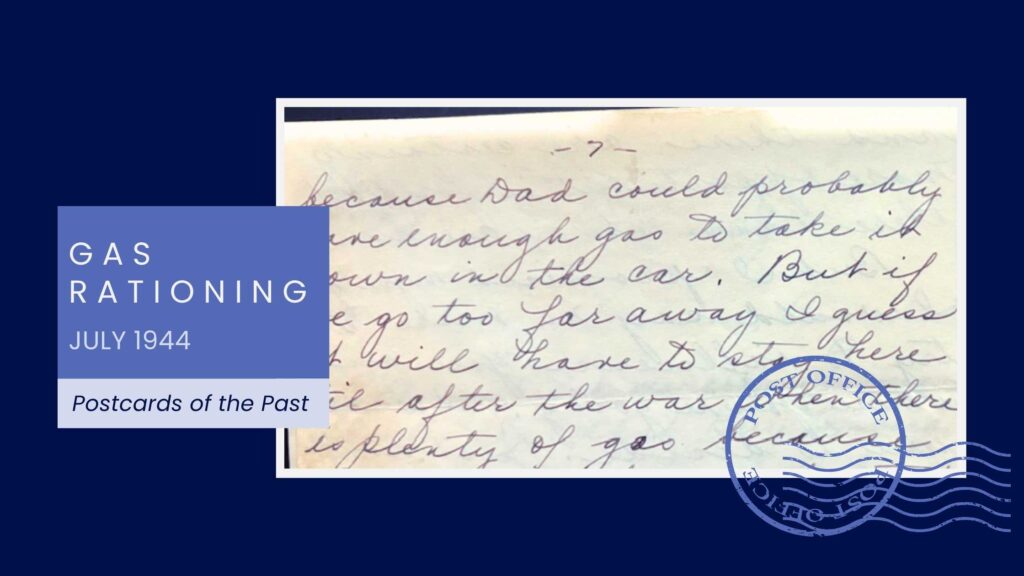

Gas Rationing

In 1944, gasoline rationing had become an accepted part of American life. Every driver carried a small ration book, and a lettered windshield sticker determined how much fuel they were permitted each week. For most families, like my mother’s, the driver had an A-ration card, the most common classification in the country. It allowed only […]