Presidential Campaigns

July 1944Dearest Reader,

My mother’s letter of July 11, 1944, contains a single line that instantly reveals just how different presidential campaigns were then compared to today:

“I see by tonight’s headlines that Roosevelt says he is going to run for a fourth term very reluctantly. Humph!”

There was no televised announcement, no rally, no choreographed campaign rollout. Instead, Americans opened their evening newspapers and discovered that Franklin D. Roosevelt had agreed to accept the Democratic nomination if it was offered. Earlier that day, he had sent a brief letter to Robert E. Hannegan, chairman of the Democratic National Committee. The letter was released to the press, and by nightfall, the headlines reached my mother in Concord, NH.

She was not a partisan voter. As she explained:

“I’m not registered as a Democrat or Republican. I’ve always voted for the man I thought best, whether he was a Democrat or Republican.”

Her words come from a time when voters learned political news from newspapers and radio, not from 24-hour coverage or social media.

When Roosevelt signaled on July 11 that he would run again, most Americans had no idea how ill he actually was. His doctors and close advisors were concerned about his hypertension, heart strain and fatigue. But this information was carefully guarded.

To the public, Roosevelt appeared tired but his physician reassured reporters that the president was in excellent health and the press of the era respected these boundaries. Most Americans had no way of knowing just how fragilehis health was.

The 1944 Democratic National Convention, held from July 19 to 21 in Chicago, made Roosevelts’ candidacy official. Conventions of that era were practical political gatherings. Roosevelt did not attend in person.

Delegates renominated Roosevelt decisively thus continuing the leadership that was viewed as essential during the Allied forces fighting in Europe and the Pacific. The convention also selected Harry S. Tryman as his running mate.

Reading the sentence in my mother’s letter to my father, has captured a snapshot of a very different political process and world. The 1944 campaign was at the intersection of war and news arrived in headlines. Campaigns were subdued and shaped by wartime responsibilities.

Today, presidential elections stretch on for months or years. Candidates announce early, raise enormous sums of money, appear in interviews and debates. The length, cost and intensity of modern elections would have been unimaginable in 1944.

By contrast, the entire 1944 campaign unfolded in what now feels compressed. Roosevelt’s decision became public on July 11, just eight days before the Democratic National Convention. Americans simply opened their evening newspapers and saw the headline: The President would run again.

Dr. Nancy Watson

Rambling With Nan

Washington

Read More From Nancy

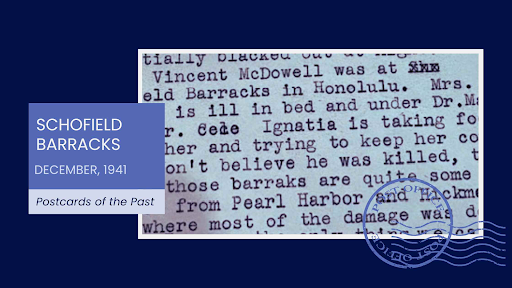

Schofield Barracks

Schofield Barracks sits in the center of Oahu, inland from the coast. Established in 1908 and named for Lt. Gen John M Schofield, the post was deliberately placed away from the shoreline to function as a permanent U.S. Army installation. It was designed for training, housing and command and not for naval operations. By 1941, Schofield […]

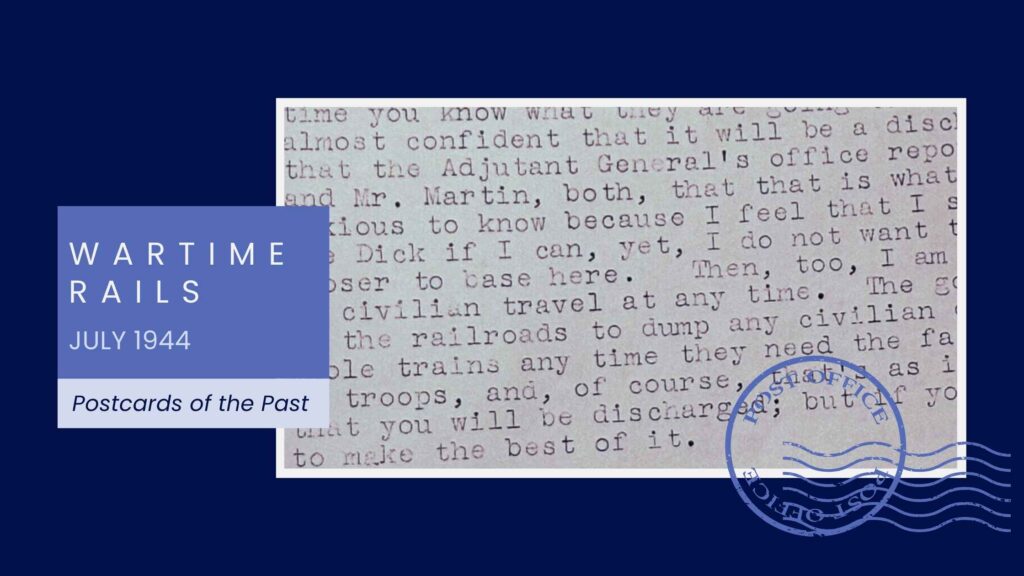

Wartime Rails

On Thursday, July 6, 1944, my grandmother sat at her typewriter once again to write to my father. It seems she wrote every day with letters mixed of small local happenings, the weather and some words of advice for her only son. In this letter her daily life intersects with the larger rhythm of a […]

Washington in Blackout

In the December 13, 1941, letter, my grandmother described another unsettling reality of those first days after Pearl Harbor, the fear that the war might reach the American mainland. Information was fragmentary, rumors circulated freely, and no one yet knew what form the conflict would take. She wrote simply and without drama: “They tell us […]